Last weekend I ran in the Liverpool half marathon with my best friend, Harry. The race was scheduled to start at 9am on Sunday 25th March, so an early night was on the cards for Saturday. Unsurprisingly to me, my sleep was disrupted by anxious thoughts of what the next day would bring. I was already pretty certain that my time would not be below 2hrs 30 and I didn’t want to hold Harry back, who had already run 2 half marathons previously. Our alarms went off at 6am on Sunday morning after a very restless night. I sleepily clambered down the stairs to make us my favourite porridge concoction – raisins, almonds, chia seeds, cinnamon; all the good stuff. I took a naproxen, which had been prescribed for my dodgy knees and gathered the essentials: energy blocks, my phone for Strava and a nice big bottle of water that I had mixed with a mineral supplement to replace all the salts I’d be losing during the race.

I felt prepared and unprepared all at the same time, and my nerves were definitely present. As we travelled down to Liverpool, I insisted to Harry that if he felt like I was holding him back to please run ahead, but of course he refused. When we got to the starting line, we made our way to the back, where the 2hrs 30 pacer was waiting to begin. We stood and chatted and laughed, there’s really nobody in this world who can make me laugh quite like Harry can, and just like that – my nerves were gone. We began running, and all of my worries about not being able to control my breathing or my knees being sore just disappeared. I was running at Harry’s pace and I was actually finding it easy! We overtook numerous people, including the 2hrs 30 and 2hrs 20 pacers. I was completely absorbed and felt amazing, I’d finally achieved flow!

Flow is described as a state of optimal experience which involves total absorption in a task and a state of mind whereby optimal performance can be achieved (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990). Csikszentmihalyi (1990) argued that there are activities and personality traits where flow would be achieved more easily, however flow can be applied to a range of different activities and is not solely applied to individuals who have had a lot of practice, such as elite athletes (Csikszentmihalyi, 1975). In a study focusing on participants who were physically inactive, high states of flow were still observed when these participants were placed in different exercise intervention groups (Elbe, Strahler, Krustrup, Wikman, Stelter, 2010). Many factors have been identified that facilitate and impede flow, and a review by Swann, Keegan and Crust (2012) identified a number of these factors. Below is a diagram of the factors listed in the review that are said to facilitate flow, and how these related to me during the half marathon.

However, the presence of my friend had been a powerful motivator for me during this race, and I wanted to discover if flow could be shared. In past research, flow has been described as an individual, not a group, phenomenon (Walker, 2010). However, recent research has actually identified the existence of social, and not just solitary, flow (Froh, Menges, & Walker, 1993). For example, joyful flow experiences were found to be present in team sport activities and creatively expressive tasks such as music (Csikszentmihalyi & Rich, 1997; Mockros & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000). Additionally, social flow has been found to elicit more joyful and elated feelings upon finishing an activity than solitary flow (Walker, 2010).

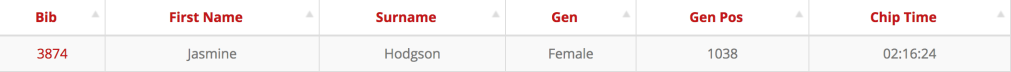

Exploring social flow has helped me understand my thoughts and feelings on that day, as my experience of flow was shared with my best friend. Likewise, the feeling of elation we both had at the end of the race was unmatchable to any feeling I’ve had during this module. It is nice to now be able to understand why those feelings of joy were so strong for us both. Although I will be running the marathon without Harry, I feel such a greater sense of confidence within myself and my capabilities. I was able to complete the race in 2hrs 16 and I finally experienced flow, something I thought would never happen! I am excited to continue my training with a new sense of self-efficacy. Bring on the marathon!

References

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1975). Beyond boredom and anxiety. San Francisco: Josey Bass.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. New York: Harper & Row.

Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Rich, G. (1997). Musical improvisation: A systems approach. In R. K. Sawyer (Ed.), Creativity in Performance (pp 43-66). Greenwich, CT: Ablex.

Elbe, A. M., Strahler, K., Krustrup, P., Wikman, J., & Stelter, R. (2010). Experiencing flow in different types of physical activity intervention programs: three randomized studies. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports, 20(s1), 111-117. DOI: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2010.01112.x

Froh, R. C., Menges, R. J., Walker, C. J. (1993). Revitalizing Faculty Work Through Intrinsic Rewards. In R. Diamond, New Directions in Higher Education, vol. 81, pp 87-95. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Mockros, C., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). The social construction of creative lives. In A. Montuori & R. Purser (Eds.), Social creativity (Vol. 1, pp 175-218). Creskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

Swann, C., Keegan, R. J., Piggott, D., & Crust, L. (2012). A systematic review of the experience, occurrence, and controllability of flow states in elite sport. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 13(6), 807-819.DOI: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2012.05.006

Walker, C. (2010). Experiencing flow: Is doing it together better than doing it alone?. The Journal Of Positive Psychology, 5(1), 3-11. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17439760903271116